Alameda whipsnake

(Masticophis lateralis euryxanthus)

By: Joshua Cho

Description and Ecology

The Alameda whipsnake is a slender, fast moving, snake with a broad head, large eyes, and a thin neck which is active during the day. Commonly called the Alameda Striped Racer.

Physical traits

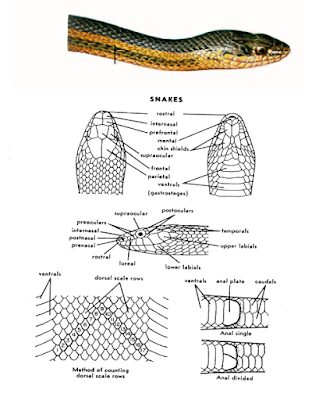

California whipsnakes have several distinguishing traits including: 17 smooth dorsal scale rows at mid body, a preocular scale wedged between upper labial scale, and a divided anal plate

Whipsnakes are generalists who eat multiple vertebrate species such as: frogs, skinks, snakes, lizards, nesting birds, and rodents. They often hunt with their head held high with semi-frequent side to side movements. Their prey is engulfed without constriction.

Diet

An Alameda whipsnakes' diet is based on its size, sex, age, and location. They particularly prefer to feed on lizards, especially the western fence lizard and optimally live in areas that support 2 or more lizard species.

Alameda whipsnakes mostly inhabit coastal shrub and chaparral communities. The existence of rocky outcroppings with deep crevices, numerous dirt burrows, or piles of brush or debris are important for overnight rest, escape from predators and heat, and foraging for food such as common rock dwelling lizards. They prefer low growing shrub communities where the canopy is generally open and shrub crown covers <75% of the land. This sparse shrub provides cover for the snakes but also sunny areas that they need. Their habitats must contain microclimates with both shade and open areas to regulate the snakes body temperature. Each snakes has a home range of 1.9-8.7 ha with generally one or more core areas centered on shrub community. They are known to frequently move in multiple directions from their core into nearby grassland, savanna, and sometimes light forests. Scientist have found no evidence of territorial behavior in this species as they overlap ranges frequently. From November to March, they hibernate due to lack of food. The snakes are very active in late summer/fall when there is more prey because of newborn lizards. The need of water for these species is unknown so it is not known if they prefer to live by open water sources.

The greatest threats to habitats is urban development of the area. Many developers bulldoze land to create residential areas or more farmland. Fire suppression also increases the detriment of wildfires. Instead if light seasonal wildfires, large fires burn through the dead plant matter creating slow and hot fires that completely burn all sources of cover. Highest intensify fires happen in summer and early fall when fuel is abundant and dry and are especially dangerous to the snake because adult and young snakes are above ground. Mining and quarrying can also directly destroy the land of the snakes.

Documents the legal fight for the snake http://www.biologicaldiversity.org/species/reptiles/Alameda_whipsnake/index.html

Conservation and Mitigation Banks established in California by the California Department of Fish and Wildlife services (CDFW)

https://www.wildlife.ca.gov/conservation/planning/banking/approved-banks

Save Mt Diablo Alameda whipsnake Video

http://www.co.contra-costa.ca.us/depart/cd/water/HCP/archive/final-hcp-rev/pdfs/apps/AppD/08a_alawhipsnake_9-28-06_profile.pdf

https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2013-08/documents/alameda-whipsnake.pdf

Sarah Swenty, sarah_swenty@fws.gov, External Affairs Divison, Sacramento Fish & Wildlife Office. “Species Information, Alameda Whipsnake.” Sacramento Fish and Wildlife, www.fws.gov/sacramento/es_species/Accounts/Amphibians-Reptiles/es_alameda-whipsnake.htm.

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2002. Draft Recovery Plan for Chaparral and Scrub Community Species East of San Francisco Bay, California. Region 1, Portland, OR. xvi + 306 pp

https://ecos.fws.gov/docs/recovery_plan/030407.pdf

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. “Species Profile for Alameda Whipsnake.” ECOS Environmental Conservation Online System, ecos.fws.gov/ecp0/profile/speciesProfile?sId=5524.

Alejandro. “Life Cycle.” Alameda Whipsnake, sites.google.com/site/alamedawhipsnakeaat2012/home.

“CALIFORNIA CHAPARRAL INSTITUTE.” Loss of Chaparral, www.californiachaparral.org/threatstochaparral.html.

Lane, Chad. “Alameda Whipsnake ( Masticophis ‘Coluber’ Lateralis Euryxanthus).” Flickr, Yahoo!, 11 June 2017, www.flickr.com/photos/chadmlane/35063388392.

McAdams, Jerry. “Oregon Trail: A Landscape-Scale Revegetation Project.” Fire Adapted Communities Learning Network, 16 Dec. 2014, fireadaptednetwork.org/oregon-trail-landscape-scale-revegetation-project/.

“Mount Diablo.” Redwood Hikes, www.redwoodhikes.com/MtDiablo/Summit.html.

“Pleasanton Ridge Regional Preserve.” Hikes Dogs Love, www.hikesdogslove.com/pleasanton-ridge-regional-preserve.html.

Scott, Diablo. “Diablo Scott's Bike Blog.” 2012 SMR 27, diabloscott.blogspot.com/2012/07/2012-smr-27.html.

Vabbley. “Masticophis Lateralis Euryxanthus, or Alameda Whipsnake.” Flickr, Yahoo!, 23 Apr. 2011, www.flickr.com/photos/vabbley/5646934800.

“Whipsnake” Alameda Whipsnake, www.biologicaldiversity.org/species/reptiles/Alameda_whipsnake/index.html.

Habitat

|

| Chaparral at Mt. Diablo |

Breeding

Each snake takes 2-3 years to reach maturity.

Their breeding season is late-March through mid-June. In this time period, male snakes are more active in movement and often are in the nearby grasslands in search of mates. Mating normally happens near the females hibernation location and the females are sedentary from March until egg laying. The females lay 6-11 eggs each season which require about 3 months incubation. They normally make nests in the grasslands in loose soil, or under rocks or logs.

Their breeding season is late-March through mid-June. In this time period, male snakes are more active in movement and often are in the nearby grasslands in search of mates. Mating normally happens near the females hibernation location and the females are sedentary from March until egg laying. The females lay 6-11 eggs each season which require about 3 months incubation. They normally make nests in the grasslands in loose soil, or under rocks or logs.

Predators

Adult snakes are mostly preyed on by diurnal (daytime active) predators but their eggs are consumed by nocturnal mammals such as rats. Several native predators include the California kingsnake, raccoon, striped skunk, opossum, gray fox and coyote. When in open terrain, they are exposed to birds such as the red-tailed hawks and when close to urbanized areas, they are susceptible to non native predators such as feral rats, cats, pigs, and dogs.

Geographic and Population Changes

Historical Location

Due to limited historical data, the past distribution of the species is complicated to determine. Scientists cannot accurately estimate past habitat with current vegetation, because the east bay area has experienced rapid environmental change within the last 100 years.

The snakes likely inhabited scrub and chaparral communities mainly in Contra Costa and Alameda county with certain occurrences in San Joaquin and Santa Clara. The oldest historical records of this snake. date back to 1950 with distributions on Mt. Diablo and Berkeley hills. By 1970, 12 confirmed observations of the snake in Alameda and Contra Costa counties.

The snakes likely inhabited scrub and chaparral communities mainly in Contra Costa and Alameda county with certain occurrences in San Joaquin and Santa Clara. The oldest historical records of this snake. date back to 1950 with distributions on Mt. Diablo and Berkeley hills. By 1970, 12 confirmed observations of the snake in Alameda and Contra Costa counties.

Current Location and Population Change

There are 6 designated critical habitat locations for the whipsnake

- Unit 1: Tilden-Briones; Alameda and Contra Costa Counties (34,119 ac (13,808 ha))

- Unit 2: Oakland-Las Trampas; Contra Costa and Alameda Counties (24,436 ac (9,889 ha))

- Unit 3: Hayward-Pleasanton Ridge; Alameda County (25,966 ac (10,508 ha))

- Unit 4: Mount Diablo-Black Hills; Contra Costa and Alameda Counties (23,225 ac (9,399 ha))

- Unit 5A: Cedar Mountain; Alameda and San Joaquin Counties (24,723 ac (10,005 ha))

- Unit 5B: Alameda Creek; Alameda and Santa Clara Counties (18,214 ac (7,371 ha))

- Unit 6: Caldecott Tunnel; Contra Costa and Alameda Counties (4,151 ac (1,680 ha))

The snakes are currently divided in 5 main population groups with fragmented regional meta-populations. Each population has varying degrees of isolation due to natural and human barriers.

Only 2 or 3 potential corridors for gene flow between the populations exist. Snakes can travel through connected hills to reach other populations through the northern or southern corridor but it is unknown if they are able to travel under raised portions of freeways. The snakes also have a source-sink dynamic with young snakes from recovering populations often dispersing into low quality habitats and either reaching other sub-populations of dying off. Specific sources have not yet been identified.Listing type and date of listing

Listed on 12/05/1997 as Threatened under section 4(a)(1) of the Endangered Species Act

Recovery plan issued on 04/07/2003. (Draft Recovery Plan for Chaparral and Scrub Community Species East of San Francisco Bay, California)

The listing was was reviewed in 2011 and no status change was suggested.

Classified under California/Nevada Region (Region 1)

Recovery plan issued on 04/07/2003. (Draft Recovery Plan for Chaparral and Scrub Community Species East of San Francisco Bay, California)

The listing was was reviewed in 2011 and no status change was suggested.

Classified under California/Nevada Region (Region 1)

Cause of Listing and Main threats to continued existence

Current threats to the species are assorted under 5 factors

- Present or threatened destruction, modification, or curtailment of its habitat or range Ex: urban development, inappropriate grazing practises, habitat alteration from fire suppression

- Overutilization for commercial, recreational, scientific, or education purposes Ex: reptile collectors, scientific studies

- Disease or Predation Ex: increased predation from native and nonnative predators due to urbanization

- Inadequacy of existing regulatory mechanisms Ex: limited protection under State law, difficulty of fire management at urban/wildland interface

- Other natural or man made factors affecting its continued existence Ex: Inappropriate grazing, spread of nonnative plants, fragmentation, genetic drift, and fire suppression creating closed-canopy habitat and increasing severity of fires

Habitat Loss

|

| Habitat loss over the years in the Oakland Hills |

|

| Interstate 580 splitting 2 critical locations |

Fragmentation

Construction of roads within largely unbroken tracts of habitat results in losses of snake habitat as well as direct mortality of snakes crushed by motorized of non-motorized vehicles. These roads, paths, and trails also pose as barriers for snakes isolating certain populations.Degradation

Fire suppression can alter the habitat of the snake by allowing plants to establish a closed canopy. This results in a cooler and darker conditions that may affect the snakes and its prey base as snakes

|

| Left: No grazing and prevalent brush Right: Goat grazing and little wildlife growth |

prefer open air. Grazing and related practises can result in significant, long term, losses of scrub vegetation that the snakes generally live in and shorter grass makes snakes an easier targets for aerial hunters. The snakes are also subject to increased predatory pressure from introduced species such as rats, feral pigs, and feral and domestic cats. These threats are especially acute when urban development is close. Introduced nonnative plants can out compete native plants and reduce suitable habitat as well as prey base. Ex: Snakes avoid eucalyptus

These threats will render the remaining habitat less suitable for Alameda whipsnakes and special management may be needed to address these threats. Many of these threats do not only fall under one category but often can be classified under multiple.

These threats will render the remaining habitat less suitable for Alameda whipsnakes and special management may be needed to address these threats. Many of these threats do not only fall under one category but often can be classified under multiple.

Recovery Plan

Recovery strategy is a combination of- Long-term protection for large sections of the snakes habitat.

- Protection of necessity areas such as population (source) centers or connection areas.

- Management considerations such as fire management, mindful grazing, control of harmful introduced species.

- Research centered on the management and recovery of the species.

Critical Habitats are the focus area of recovery efforts

When federal land contains critical habitats, they must: make sure that actions they fund, authorize, or perform will not destroy or modify the habitat, evaluate their actions in respect to any threatened or endangered species and their habitats, and talk with the Fish and Wildlife Service before performing any actions that can effect the species or their habitatWhat can you do?

- Stay on trails. Going through undeveloped land may result in both losses of habitat and direct mortality to the whipsnake Ex: horseback riding, offroad driving and biking

- Be considerate when you deal with fire of any sort, a cigarette butt or a spark from a fire pit can ignite a wildfire in the very flammable dead material in many areas

- Petition local government to increase the amount of designated critical habitat for the snakes and request for a limitation of urbanization on or near designated habitat.

- Volunteer in trips to look for endangered animals in local parks. Having knowledge of exact locations of species and their populations can be important factors in the planning and success of preservation plans.

- Keep pets on leashes when hiking or walking through the hills. Although you may think that it is open land and pets roaming will have no impact, pets can easily can destroy snake habitats and kill the snakes directly.

- Leave natural objects where they are, moving a large log to cross a stream or kicking brush for fun may expose a whipsnake habitat and destroy keystone elements of their habitat.

- Use social media to raise awareness of the issue. Especially important if it is a local species that many of your friends will know about.

Personal Comments

I chose this snake because of its proximity to my home location. I have hiked the majority of the critical habitat areas and have seen many snakes - though I do knot know if the whipsnake was one of them . For me, its important to know about the threatened species in my vicinity so I may be able to aid the community in service projects and other ways.

Other resources?

Conservation and Mitigation Banks established in California by the California Department of Fish and Wildlife services (CDFW)

https://www.wildlife.ca.gov/conservation/planning/banking/approved-banks

Save Mt Diablo Alameda whipsnake Video

Rare sighting of the Alameda whipsnake

Extra Photos

Citations

Research

“Alameda Whipsnake (Masticophis Lateralis Euryxanthus).” East Contra Costa County HCP/NCCP, Oct. 2006.http://www.co.contra-costa.ca.us/depart/cd/water/HCP/archive/final-hcp-rev/pdfs/apps/AppD/08a_alawhipsnake_9-28-06_profile.pdf

Beacham, Walton, Castronova, Frank F., and Sessine, Suzanne (eds.), 2001. Beacham’s Guide to the Endangered Species of North America, Gale Group, New York. Vol. 1, pp. 650–652.

https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2013-08/documents/alameda-whipsnake.pdf

Sarah Swenty, sarah_swenty@fws.gov, External Affairs Divison, Sacramento Fish & Wildlife Office. “Species Information, Alameda Whipsnake.” Sacramento Fish and Wildlife, www.fws.gov/sacramento/es_species/Accounts/Amphibians-Reptiles/es_alameda-whipsnake.htm.

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2002. Draft Recovery Plan for Chaparral and Scrub Community Species East of San Francisco Bay, California. Region 1, Portland, OR. xvi + 306 pp

https://ecos.fws.gov/docs/recovery_plan/030407.pdf

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. “Species Profile for Alameda Whipsnake.” ECOS Environmental Conservation Online System, ecos.fws.gov/ecp0/profile/speciesProfile?sId=5524.

“7 Endangered Species That Hurt Land Values [Bay Area].” California Land Development, 3 June 2017, californialanddevelopment.com/2017/06/7-endangered-species-that-hurt-land-values-bay-area-edition/.

Pictures

“CALIFORNIA CHAPARRAL INSTITUTE.” Loss of Chaparral, www.californiachaparral.org/threatstochaparral.html.

Lane, Chad. “Alameda Whipsnake ( Masticophis ‘Coluber’ Lateralis Euryxanthus).” Flickr, Yahoo!, 11 June 2017, www.flickr.com/photos/chadmlane/35063388392.

McAdams, Jerry. “Oregon Trail: A Landscape-Scale Revegetation Project.” Fire Adapted Communities Learning Network, 16 Dec. 2014, fireadaptednetwork.org/oregon-trail-landscape-scale-revegetation-project/.

“Mount Diablo.” Redwood Hikes, www.redwoodhikes.com/MtDiablo/Summit.html.

“Pleasanton Ridge Regional Preserve.” Hikes Dogs Love, www.hikesdogslove.com/pleasanton-ridge-regional-preserve.html.

Scott, Diablo. “Diablo Scott's Bike Blog.” 2012 SMR 27, diabloscott.blogspot.com/2012/07/2012-smr-27.html.

Vabbley. “Masticophis Lateralis Euryxanthus, or Alameda Whipsnake.” Flickr, Yahoo!, 23 Apr. 2011, www.flickr.com/photos/vabbley/5646934800.

“Whipsnake” Alameda Whipsnake, www.biologicaldiversity.org/species/reptiles/Alameda_whipsnake/index.html.